James Cowan (9 April 1942 – 6 October 2018)

The following essay was written to commemorate the life and work of my friend, the visionary writer James Cowan. It was first published in the ‘New Dawn’ magazine in its March-April 2023 edition. I share here publicly to celebrate the 82nd birthday of a friend and fellow explorer of the mystic way.

Streams are the eyes of a landscape.

– Novalis

The author, poet, and traveler James Cowan was in pursuit of the metaphysical vision for most of his life. He even attempted to define a new literary genre with it – one that he called metaphysical realism. In his own words, he had been grappling with the concept of metaphysical realism for more than fifty years. He recognized that the ordinary realist perspective of the world had served us well; but that it had also proved to be one of limitation. Cowan felt that it had ultimately diminished the importance of the imagination. The modern age was seen to be dominated by action and the outward gaze. How the mind works inwardly through the intellect – to contemplate how and why things should be done – was, according to Cowan, being neglected and superseded by the imminently practical. The development of the mind’s inner powers began to mean less and less to modern humanity. James wrote, ‘I had to find a way whereby my creative intellect might acquire space in which to operate. I soon understood that my thought needed to contemplate forms that were timeless if I were ever to bring into fruition a more robust form of fictive expression.’[i] Words had to be ‘not simply comprehensible markings on a page’ but ‘photons capable of irradiating the mind of a reader…’[ii]

James felt that he needed a way to access a different form of consciousness. In his own words, he felt he was left with no choice:

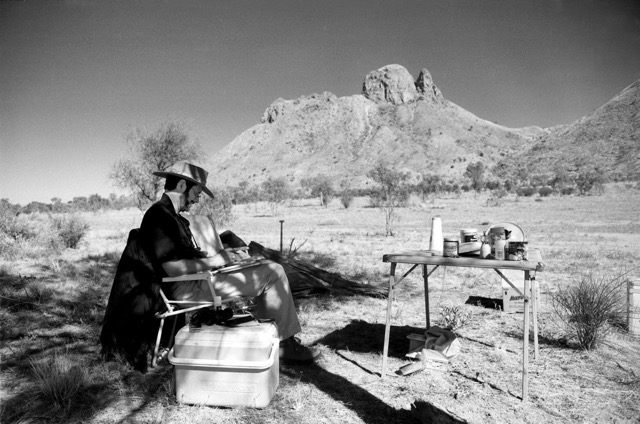

I was left with no choice but to find another way of dealing with time in the context of creative fiction. It was then that I made the decision to return to a period in social history when time did not exist as a framework for human existence. I journeyed into Central and northern Australia to begin my encounter with elderly Aboriginal tribesmen in order to understand how they viewed time in the context of their Dreaming narratives.[iii]

This was how James Cowan began his adventures into the Aboriginal landscapes of the Dreaming. James began to learn from the Aboriginal Elders how myth could be used as a vehicle for metaphysical expression. Through his Dreaming journeys in the desert the raw young artist was shown how landscape and language worked in tandem. Words were ‘more than cerebral;’ they also contained the residue of an endlessness that had become embedded into the physical artefacts of our human realm. Cowan began to read classic tales as that of Gilgamesh, the Arthurian legends, and early Coptic hagiographies of desert anchorites – realms that were inhabited by the miraculous. The idea was to seek out examples of a timeless construct where the very best of human nature could find experiences to nurture it. James spent several years living, travelling, and learning from the Aboriginal culture. This culminated in several well-received books, including Letters from a Wild State: An Aboriginal Perspective (1991), The Element of the Aborigine Tradition (1992); Myths of the Dreaming: Interpreting Aboriginal Legends (1994); and Two Men Dreaming: A Memoir, A Journey (1995). In the 1990s, James spent two years living in Balgo Hills, a remote Aboriginal settlement in the Tanami Desert where he had set up a cultural institute to promote and sell the work of Aboriginal painters.[iv] James considered the Aboriginal artists of the Balgo Hills to be among the most innovative painters working in Central and Western Australia. When I asked him why he had chosen to go from the life of a writer to that of an art coordinator, I received an unexpected reply. He told me he had wanted to pay back his debt to the Aboriginal community. What debt? I asked. They had given me their stories, he had said. When an Aboriginal Elder shares with you their story, they are giving something from their community, and they too incur a debt. Their stories are their community possessions, their treasures. You cannot treat them lightly. They gave me great gifts over the years, and this debt I feel I must pay back. And I am doing this by promoting their work to the world. It is the least they deserve. It was a humbling reply. And it was indicative of how James viewed the world. It was not a solid place, peopled by physical objects and remnants. It was a living mythos. And it ran on the power of stories.

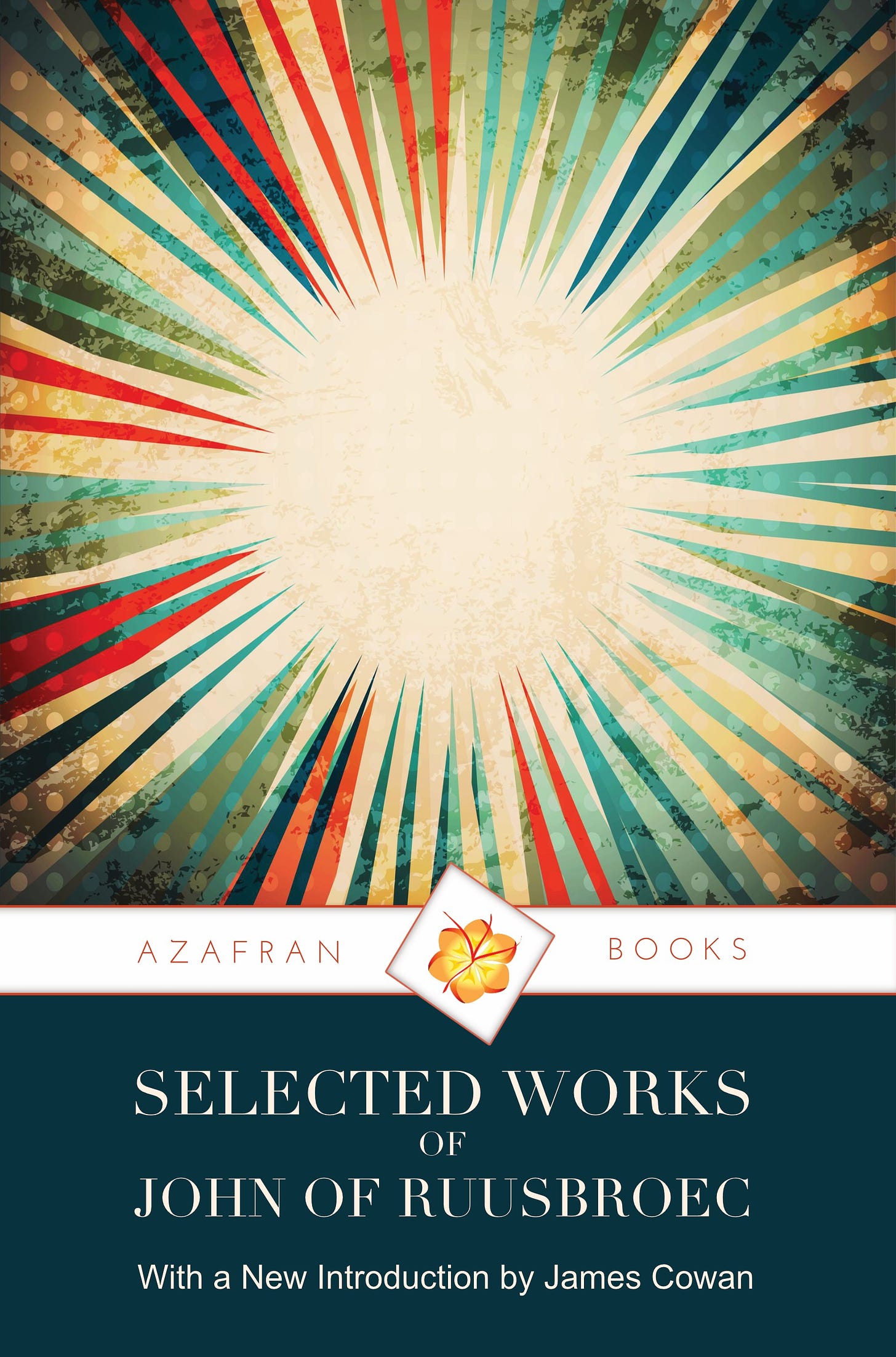

During the 1990s James also went to visit the village elders and shamans in the longhouses of Borneo. He saw how these tribes ‘stored’ narratives through the random juxtaposition of storyboards on the floor of their longhouse. These storyboards were ‘like wafers: on them were a rudimentary script made up of markings.’ Rather than being confined to the rigor of sacred texts, language could be placed in the category of uncertainty. The patterns that were found in nature transcended the literalness of words placed on paper, and myths could find new a new dance of life to transmit their secrets. James wrote up his experiences among the natives of northwestern Australia, Borneo, and the Torres Strait Islands in his book Messengers of the Gods: Tribal Elders Reveal the Ancient Wisdom of the Earth (1993). To further polish his learning, James reread ancient and medieval texts, particularly those associated with the development of early philosophy and theology. He discovered that writers of these periods had developed a way of saying something by referring to what it is not (what he called theory of apophasis). James felt himself at home amongst the medieval writers, many of which stayed with him throughout his life. Writers such as Dionysius the Aeropagite (late 5th–6th c. AD), John Scotus Erigena (815–877), Ibn Masarra (883–931), and John of Ruusbroec (1293–1381).

True language, James felt, should be able to express itself not only in new and exceptional ways but also in a manner that the reader may not be accustomed to. He didn’t wish for thought to be subjected to the constraints of language; and in order to reconstitute a reality of a higher order, he first had to disrupt the current mode of expression. Language was seen as an incantation. This was the aim of James Cowan’s metaphysical realism – to tell a story within a story. And this meant it was necessary to dispense with the objective realism of storytelling. In James’ writings, telling a good story alone was not good enough. Western materialism, he felt, had exhausted the notion of the unending linear narrative. It was necessary to investigate an inner dimension that is timeless, regardless of whether it goes against literary tradition. James was seeking to capture the essence of the inward event within the experiences of the human condition. And in doing so, he realized that his work may be regarded as subversive for it was willing to go against the grain of what is considered reality. Yet James Cowan was not the first writer in history to expound metaphysical realism. According to James, metaphysical realism, as a creative method, was first acknowledged by Parmenides in the sixth-century BC. He wrote a philosophic poem, ‘Way of Truth,’ which formulated the principles of logic that continue to govern our thought today. His poem profoundly influenced thinkers such as Socrates, and later Plato, because he paved the way for them to develop a system of logic that we now use. James felt that Parmenides was the first to present the idea of the way, the path, as a new form of narrative; an idea later shared by Peter Kingsley.[v]

A chariot bore me as far as my heart desired

Urging me upon the Way of the Goddess

That leads wise men from town to town.

On that Way I was hauled by trusty steeds

Hitched to a chariot, & driven by maidens.

Its axle glowed fiery red in their hubs, heated by

Spinning wheels at each end, both emitting sounds

Of a panpipe, while the Daughters of the Sun

Wishing to transport me into the light, tossed aside

Veils from their faces as we left Night’s abode.[vi]

Such writing as given by Parmenides makes the reader aware that there is a way to rise to a certain state of being. And upon this path there is one thing of supreme importance: the human imagination. It is through the imagination that a person can break from the real to venture forth into the realm of the spirit. James realized that this was the same technique used by Aboriginal Elders, and other natives such as the Iban people, that he had spent time amongst. It is a path that enables the listener/reader to enter into the world that exists within the underlying language. This was the realm of the divine utterance – the very essence of metaphysics. Writing, for James, was a pathway to reach into these ‘divine utterances’ in a bid to understand, and consequently to present, the revelations of transcendent experience through language. James was well aware that he would never fully master this technique. Yet he put his hand to the task.

In 1996 the world was presented with A Mapmaker’s Dream. I remember James laughing gently as he told me the tale of how his most widely read book came into publication. He said he had sent it to various publishers but none of them knew what to make of it. Saddled with an unusual book, just about every publisher preferred not to take the economic risk; so they put it aside. Except one. The editor of Shambhala Publications finally gave James a call. He told James how they had read the book, enjoyed it, yet thought it was unmarketable. And so, like every other publisher, they had put the book aside. Yet, a strange thing happened. Each person at Shambhala who had read the book could not stop thinking about it. It would not leave their thoughts. It hung around in their heads, lingering like the vestiges of some peripheral dream. It would not let them go. Finally, the editor knew the book had to be released. He was on the phone now with James, asking if he would sign their contract. ‘I’m going away in a couple of days on a journey,’ James replied. ‘Maybe when I get back I can look over the contract.’ There was a pause on the other end of the phoneline. ‘Too late,’ came the reply. ‘I’ll fly over to Australia tomorrow and you can sign the contract.’ James was bemused. As good as his word, the editor at Shambhala Publications flew from America to Australia and handed the contract to James. He signed it, then went off on his trek. James was not expecting the future success that A Mapmaker’s Dream would generate. The book, being ‘The Meditations of Fra Mauro, Cartographer to the Court of Venice’ (to give its full subtitle) explored a whole world across time and space. In my own PhD thesis, almost fifteen years before finally meeting James, I had quoted from A Mapmaker’s Dream as an opening citation to my chapter on hyper-complexity. I quoted:

‘Every man who had ever lived became a contributor to the evolution of the earth, since his observations were a part of its growth. The world was thus a place entirely constructed from thought, ever changing, constantly renewing itself through the process of mankind’s pondering its reality for themselves … No continent or people have turned out to exist except in relation to themselves. Their geographic location has also proved to be deceptive. The inescapable conclusion is that the true location of the world, of its countries, mountains, rivers, and cities, happens to lie in the eye of the beholder’[vii]

A perfect reflection of our inter-connectivity as a global species: geographic location has ‘proved to be deceptive.’ Our world – that is, our reality – is a place entirely constructed from thought. As such, it is ever changing, and constantly renewing itself. This is our world perfectly described. Everything within it, including ourselves, only exist in relation to one another. Everything thus lies within the eye of the beholder. We are the mapmakers, and we are each living through our dreams. The story of the world is told more through the languages, thought, and beingness of its characters (us) rather than in the do-ing of the characters. And this was what James reflected in his writings; especially so in A Mapmaker’s Dream which was perhaps his own first full exposition of metaphysical realism. Commercially, it was a success. A success that James was not to repeat in his lifetime.

A Troubadour’s Testament (1998) followed from this.[viii] The book was another journey: a contemplation of love enacted both outwardly and through the inward gaze. ‘Solitude is a difficult encampment,’ wrote James within its pages. ‘Its guy ropes grow rigid on frosty mornings.’ James was exploring the soul as a solitary substance: ‘it wanders through space, a lonely at times disfigured star, torn this way and that as it struggles to maintain its course.’ James felt compelled to pursue his metaphysical vision through the struggle of the human soul. His next series of books turned away from fiction towards an outer and interior travelogue of how the human heart and soul endures and finds nourishment through the world: Journey to the Inner Mountain: In the Desert with St. Antony (2001);[ix] Francis: a Saint’s Way (2002); and Fleeing Herod: through Egypt with the Holy Family (2013). By this time, James had decamped and left Australia to live in Italy for several years, to absorb the culture, learn the language, and to research the life of Saint Francis. James’ vision was to explore the world through whispers rather than shouts. To probe into the phantasms of the human soul; to trace the movements of an ant’s foot across a black stone in the darkness of night. According to James, the metaphysical vision is ‘a rare flower’ – Novalis’s blue flower, perhaps? He respected the writings of Novalis, Friedrich Hölderlin, Victor Segalen, Borges, and later, W.G. Sebald. He saw all such writings as seeds that were seeking their cultivation through the reader. James’ own wish in his writings was to create a realm to allow the reader to change places with himself. The reader, he felt, should not be required to remain bound by the limits of his or her world perspective.

James lived the final months of his life as a literary meditation. The Book of Letters was the last completed full work from James Cowan. It was written during his final months, and he intended it to be his ultimate testimony and love letter to the sanctity of language. Of this book, he said:

It is a pure work, and goes to the heart of our time. We have distanced ourselves from the purity of language, hence the grave time in which we live. The Book of Letters is a cris de coeur for a return to the sanctity of words … my final attempt at genuine metaphysics of language.[x]

And still, the metaphysical gaze would not rest. James began working on a new composition in the final weeks of his life, which was left almost completed. Within the scarcity of life, James was more concerned with thoughts than with titles. James had no name for the final book he was composing: ‘The question I next asked myself was: what should I call it?’[xi] And so, the book became the Liber sin Nomine (a book without name). It was James’ original intention to create a type of spirit-full collection, or sacred ‘tag-ends of my own thoughts.’ In his final days, he spoke of the book as an ongoing flow of thoughts and aphorisms. He often referred to it as ‘my Aphorism book.’ Yet it was more than a humble collection of ‘tag-ends.’ The book became James’ own meditation on death and dying, and the relationship between a sacred life and the passing of that life. Within the book there are various places where James is acutely aware of the nature of his dying body – also, the rebellious behaviour of his body. He states that, ‘Let there be no mistake: my body has chosen to leave me! I did not give it permission to depart, at least not yet.’[xii] Here are the words of a heart and mind, an active and alert consciousness, coming to terms with a disintegrating, and dissenting, body: ‘My body, now, is in violent disagreement with me. It simply refuses to concur with my pre-disposition towards health.’[xiii]

The book without name is a reflection on the act of dying. As a person who spent his whole life seeking to unravel the sacredness and mystery of life, James was now the participant in his own passing, and witnessing first-hand the departure from a world he so lovingly, and desperately, sought to embrace. Ultimately, the writing of this final book was a tool that allowed him to realise his death consciously rather than through an unconscious submission. As within his own writings, James was preparing the mind for new vision, for an extension of consciousness. The metaphysical vision of James Cowan was forever attempting to ‘cut away dead flesh’ in order to get at the essentiality of words and their meaning. And this was perhaps his route to self-revelation.

[i] ‘Metaphysical Realism in Modern Literature’ (unpublished)

[ii] ‘Metaphysical Realism in Modern Literature’ (unpublished)

[iii] ‘Metaphysical Realism in Modern Literature’ (unpublished)

[iv] Balgo: new directions (Craftsman House, 1999)

[v] Reality by Peter Kingsley (The Golden Sufi Center, 2003)

[vi] One. Parmenides and his Vision. Trans. by James Cowan (Balgo Hills Publishing, 2022).

[vii] A Mapmaker’s Dream (1996). In 1998 Cowan was awarded the prestigious Australian Literature Society’s Gold Medal for this novel.

[viii] A Troubadour’s Testament (Shambhala Publications, 1998)

[ix] Later republished as Desert Father (2006)

[x] THE BOOK OF LETTERS: A meditation on the alphabet (Balgo Hills Publishing, 2020)

[xi] Liber sin Nomine (Balgo Hills Publishing, 2020)

[xii] Liber sin Nomine (Balgo Hills Publishing, 2020)

[xiii] Liber sin Nomine (Balgo Hills Publishing, 2020)